Kiko Barzaga’s playbook: When shitposting becomes a political tool

Read more

The Cavite congressman posts up to 30 times a day and has gained over 350,000 Facebook followers in a month. Here’s how he surfed a pro-Duterte wave to virality.

MANILA, Philippines – Neophyte congressman Kiko Barzaga has been on a shitposting spree. Within a month of leaving his political party, he shared over a hundred incendiary posts pitting himself against government officials — from the President to his colleagues in Congress. Cat emojis are layered over their faces, quotes stripped of context, and in one case, an AI image of Senate President Tito Sotto was even used.

Data analysis of Barzaga’s online content, as well as interviews with experts and Barzaga himself, suggest a deliberate strategy at social media growth and attempt to hack public attention. His posts are shared consistently by the top hyper-partisan pro-Duterte bloggers, suggesting at least semi-coordinated activity. In one month between September 24 and October 24, his official page jumped from 501,000 to 868,000 followers — a roughly 73% increase.

Barzaga has walked back on his 2022 support of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. and emerged as the Gen Z darling of the Duterte camp. His online conduct resulted in an ethics complaint at the House of Representatives — but it also substantially increased his viral visibility, with mentions of his name on public Facebook posts jumping to over 11,000 in September, up from only a few hundred in the previous month. His posts in September also reached over 6 million combined interactions, or roughly around 21,000 interactions per post.

The 27-year-old self-proclaimed “Prince of Dasmariñas” and “Congressmeow of Cavite” — descriptions in his online material and bio notes — also came under fire for viral photos of him holding wads of cash to his face and surrounded by women. He skipped his own ethics hearing due to gaming, claims that he faces a case from Forbes Park residents following his call to protest there, and most recently, was delisted as an Army reservist due to posts the Armed Forces deemed were “insinuating sedition.”

In an exclusive interview, Barzaga did not object to the idea that his content was “shitposting,” colloquial Internet language for intentionally disruptive and provocative content. He said he creates and posts all his content himself, save for help from his staff in laying out graphics.

“Evidence is only necessary if we’re fighting within a court of law,” said Barzaga, when asked how he would respond to criticism that his posts could be misleading or factually inaccurate. “Why would I fight in a way that is much more beneficial and much more convenient for the Marcos administration, when I can…engage the public in a way that targets the weakness of the Marcos administration?”

“If my conduct online reflects badly on [Congress], then how come they keep stealing? I think that reflects worse on them,” he added, referring to his colleagues and the ethics complaint against him. “My online conduct is ultimately harmless.”

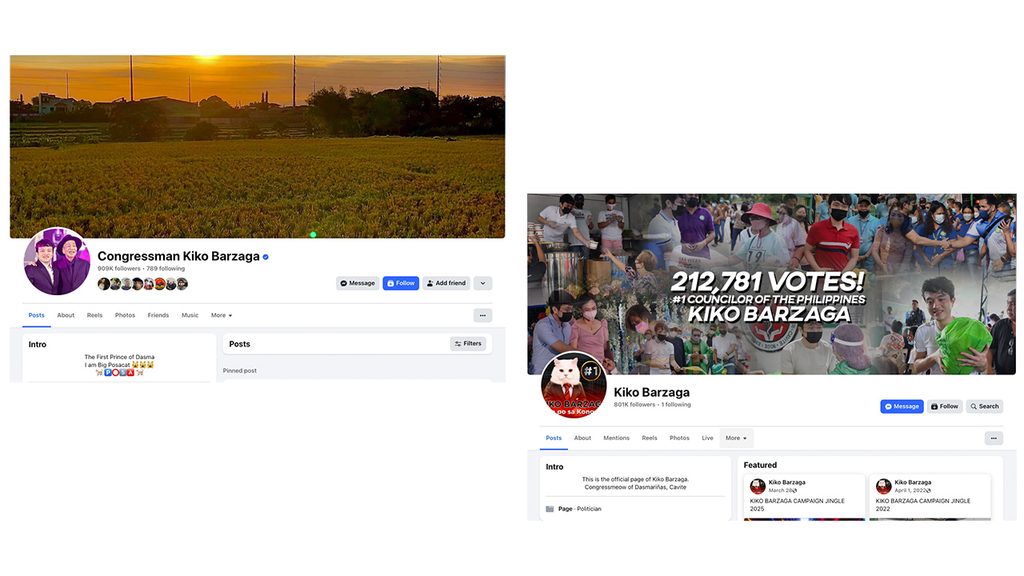

Mass memefication and routine ragebait

Barzaga has two Facebook accounts: one page for official Congress matters (Kiko Barzaga), where he often posts quote graphics against other officials, and a more personal, verified profile (Congressman Kiko Barzaga), where he has posted consecutive comic graphics and text statuses that read like a stream of consciousness. His posts often rack up tens of thousands of interactions.

Barzaga’s verified profile currently has over 900,000 followers, while his official page has over 800,000. In both of his accounts, Barzaga presents himself with a memetic persona that often incorporates cat-themed elements, making himself relatable to younger generations and different from other politicians.

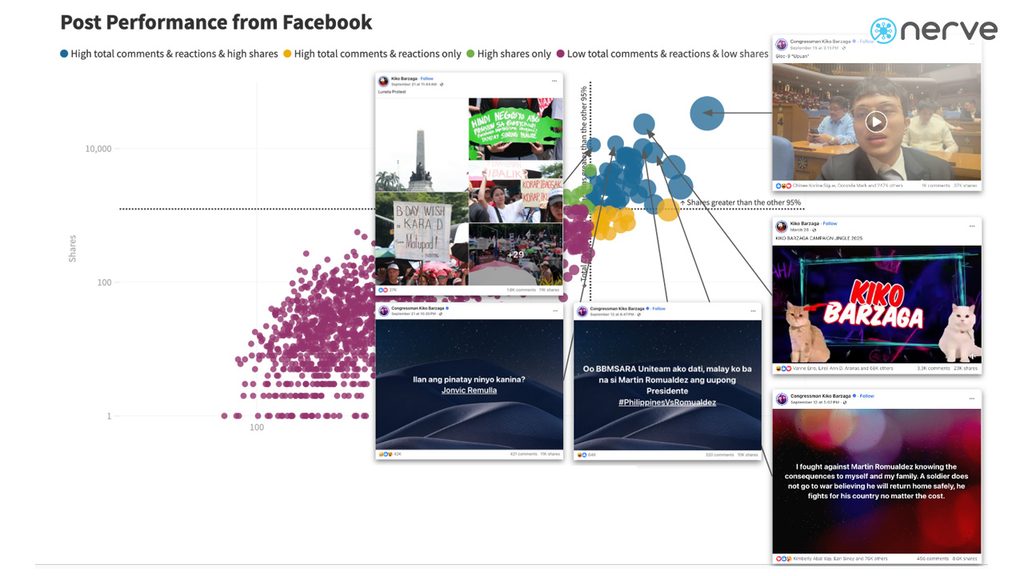

Posts from his verified profile have regularly performed better compared to his official page. In collaboration with data forensics firm The Nerve, we found that four out of six of Barzaga’s top-performing posts from September 2024 to September 2025 — or those that got above average shares, comments, and reactions — came from his verified profile.

In these top-performing posts, Barzaga talked about high-conflict political drama, such as the controversy surrounding Leyte 1st District Representative Martin Romualdez and the September 21 protests. He also openly tags other politicians in his posts, creating an impression of boldness and confrontation that amplifies his online presence.

In terms of volume, however, Barzaga consistently uses his official page to maintain engagement through a steady stream of content. A review of Barzaga’s posts in the past year showed that while posts from his verified profile were more engaging, he used his personal page to drive his overall visibility. The Kiko Barzaga page accounted for the majority of his posting activity at 81% of his total posts in 2024, while the Congressman Kiko Barzaga profile contributed 19% in terms of post volume.

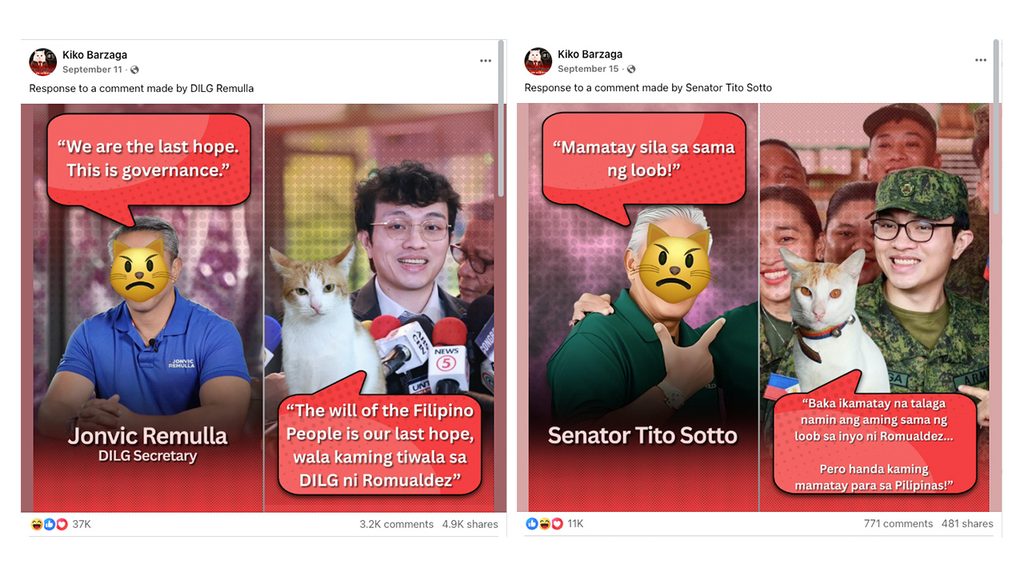

In his signature quote card template where Barzaga pits himself against other politicians and responds to them, there are no labels for when and where soundbites are said. As a result, government officials are easily taken out of context.

One such example is a September 11 post where Interior Secretary Jonvic Remulla is quoted as saying, “We are the last hope.” He was referring to an unrelated 911 system launch where he had preceded what he said with, “We are the first responders.” Barzaga, however, responded by bringing up Romualdez even if it was unrelated to the original post, and racked up some 37,000 reactions and almost 5,000 shares.

In a more recent post, Barzaga accused Marcos of ordering the fire that hit the Department of Public Works and Highways office in Quezon City. “Well, if it wasn’t President Marcos, then I wonder who else it could be,” Barzaga told Rappler, when asked if he had proof. He later added, “One of my cats told me. Meow.”

The post followed another status where Barzaga echoed a claim that the military had some ₱15 billion in ghost projects, which was disputed by the AFP.

Such posts are risky because Barzaga is “doing a tango with fake news,” said political strategist Alan German, “but the very foundation of his posting is to get a reaction, not to convert. Just to agitate, to stir the pot.”

Using natural language processing, a technique that clusters posts together based on their semantic similarities, The Nerve found that over 27% of Barzaga’s posts from both accounts contained personal updates, satire, and humorous content true to his brand.

Another 9.2% were specifically about Romualdez, whom he had previously portrayed as a symbolic rival in his perceived political victories.

Several of the top shared posts from Barzaga’s two accounts were about Romualdez and his cousin, President Marcos, where he mixed mockery and political commentary — from making fun of Marcos’ ₱20-kilo rice campaign promise to corruption allegations against them.

Experts say this type of messaging is not random, but strategic simplification. Memes can reinforce pre-existing feelings, whereas facts require more complex thought.

German said Barzaga’s posts resonate because of genuine outrage mixed with entertainment appeal. “He’s not taking himself seriously at all,” said German. “More than spreading his message, his content is curated to really elicit a reaction.”

Katrina Stuart Santiago, a Vera Files contributor who monitors the pro-Duterte TikTok algorithm, finds Barzaga’s content style reminiscent of the blogger-propagandists of the Duterte presidency.

“They were doing shitposting, ragebaiting, memefication of sociopolitical economic issues for six years,” said Santiago. Since the Marcos administration has opted for a more professional official communication, that sort of content has now been relegated to vlogs by pro-Duterte content creators — but, Santiago observed, Barzaga is reviving that style on scale back on Facebook.

Barzaga is also chronically online, sometimes posting as many as 33 times a day. Social media platforms reward this frequency, experts say. Volume feeds visibility — in turn creating influence.

“When you want to get into the algorithm of a particular subject matter, you do a mass drop of five or ten videos at the same time,” said Santiago. “That’s how Barzaga’s content felt like.”

Overlap with the Duterte network

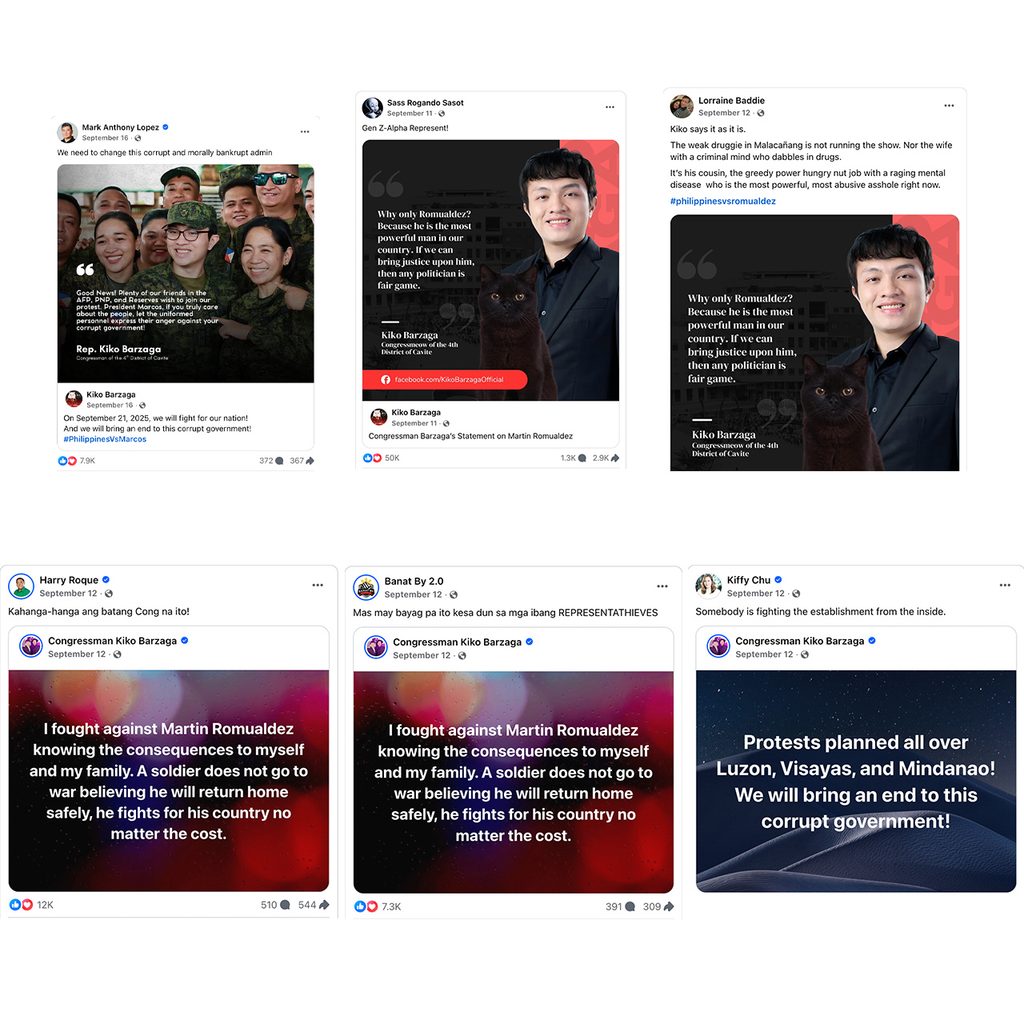

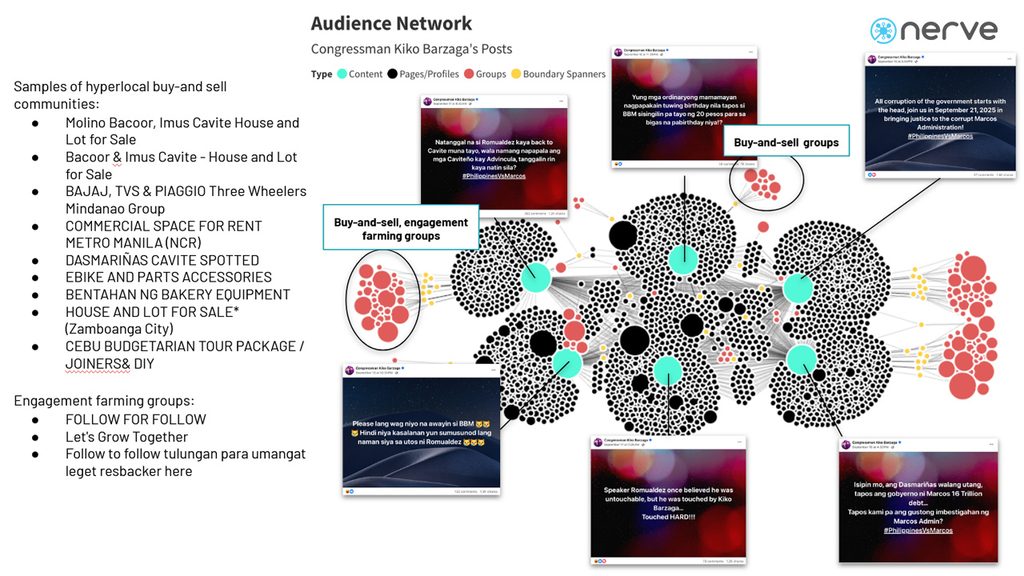

An analysis of the shares of Barzaga’s top-shared posts showed that they were funneled by different users into specific online groups and communities, including pro-Duterte communities and niche, non-political spaces such as buy-and-sell and engagement-farming groups.

These groups served as amplifiers, allowing Barazaga’s content to circulate beyond his audience base.

Apart from hyperpartisan groups, several known pro-Duterte personalities were also found to have amplified Barzaga’s posts. These include Sass Rogando Sasot, Lorraine Badoy (“Lorraine Baddie” on Facebook), Mark Anthony Lopez, Krizette Laureta Chu (“Kiffy Chu” on Facebook), Banat By (real name: Lord Byron Cristobal), and Harry Roque — further extending their exposure to politically-active networks aligned with the Dutertes.

Santiago said Barzaga became an additional resource and personality among pro-Duterte propagandists. On TikTok, she observed, Barzaga was helpful filler content on the pro-Duterte algorithm in the absence of news updates coming from the Duterte children and the International Criminal Court.

“While he isn’t particularly pro-Duterte, he is anti-Romualdez, anti-Marcos and saying all the right things that Duterte propagandists have also been saying all this time…Useful siya sa kanila (He’s useful to them),” said Santiago.

Apart from these political spaces, Barzaga’s posts also reached non-political communities, such as buy-and-sell pages and engagement-farming groups. These are online communities where users share content primarily to boost interaction metrics or attract traffic.

Previous studies have shown that seemingly non-partisan online spaces have been exploited to spread and amplify political content, enabling the proliferation of “disguised propaganda.”

Barzaga told Rappler he was not politically aligned with the Dutertes on every issue, citing Duterte’s pro-China policy, handling of the pandemic, and Pharmally. However, he saw flood control corruption as more pressing and damaging. “The problem is that the previous Duterte issues, when compared on the relative scale to the current issues we have now…it’s not the same level of corruption,” he said.

“I don’t have any personal conflict with the Dutertes,” he added, when asked if he would be open to calling out the family on issues where they diverged. “So I don’t think there’s any strategic benefit in fighting them.”

Reacting to amplification by pro-Duterte influencers, Barzaga said, “It’s not just pro-Duterte. Practically everyone’s amplifying me.”

The ‘enshittification’ of political communications

Official government use of “shitposting” was notably mainstreamed through memes and AI slop in White House accounts under Donald Trump. In the Philippine context, the Department of the Interior and Local Government under Secretary Jonvic Remulla has been criticized for using colloquial, unserious language in typhoon announcements. Pro-Duterte accounts’ widespread celebration and framing of Barzaga demonstrates a similar downturn in professional political communications.

The trend points to “enshittification,” a term coined by Canadian journalist and science fiction writer Cory Doctorow to describe platform decay. Enshittification happens when profit, often defined by engagement, starts driving the user experience of a digital product. In the Philippine case, government personalities are incentivized to sacrifice clarity for clickbait on social media.

Santiago pointed out that traditional media unwittingly amplifying a personal agenda is troubling. Prevalent in the pro-Duterte algorithm, she said, are Barzaga’s interviews with broadcast veterans Jessica Soho and Korina Sanchez. However, on other platforms such as Reddit, condemnation of Barzaga is widespread — suggesting that his appeal has limits.

German said that while Barzaga’s style may succeed in racking up engagement, it is likely to have a low conversion rate as the public will still seek evidence and offline performance. The deployment of memes in political communications should be carefully considered, he added. If the content is not substantiated, one political color might “hail you as a patron saint…but other political colors will see you as just that: a source of entertainment…but not someone to follow or emulate.”

On the flip side, memes can also have staying power, and be repurposed for protest, used to shape national conversation.

Political communications, German said, is about clearly articulating matters of state policy, direction, and advocacy. “[With] the enshittification of political comms, the overriding goal [becomes] to engage and make [content] viral,” said German, adding that policy direction suffers when virality takes precedence over substance.

If his content is libelous or offensive, Barzaga said others are free to file cases against him — but “we can’t really expect for their cases to gain much support,” he said. “At the end of the day, what the people would be questioning is, why are they fighting a case against me and not people like Romualdez?” – Rappler.com

Data, analysis, and visualization by Mark Gomez and Alan Mark Bundoc.

This story was originally published on Rappler on October 28, 2025.

Decoded is a Rappler series that tackles Big Tech not just as a system of abstract infrastructure or policy levers, but as something that directly shapes human experiences. It is produced by The Nerve, a data forensics company that enables changemakers to navigate real-world trends and issues through narrative and network investigations. Taking the best of human and machine, we enable partners to unlock powerful insights that shape informed decisions. Composed of a team of data scientists, strategists, award-winning storytellers, and designers, the company is on a mission to deliver data with real-world impact.

.jpg)